American Jews and the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies

When we inventoried the 1926 U.S. Census of Religious Bodies schedules at NARA, we noticed one glaring omission. The schedules for Jewish congregations were missing.

A glance through the comments on Jews in the published census volumes revealed other oddities. In 1916, the Bureau counted approximately 357,000 members of Jewish organizations. In 1926, the Bureau reported a Jewish membership of more than 4 million. The bureau itself noted that “it would be fallacious to assume that this increase of 3,724,107 represents the [actual] growth in Jewish membership during the decade.” Clearly, something was amok.

From the outset of the Religious Bodies censuses, the fact that different denominations and religious groups counted membership differently posed an enormous challenge. Back in 1890, when questions about church membership were conducted alongside the decennial population census, the Bureau had attempted to impose a uniform standard of membership. “Communicants,” it declared, “are to be considered all those, without distinction of sex, who are permitted to partake of the Lord’s Supper in denominations observing that sacrament, and those having full privileges in denominations such as Friends, Unitarians, Jews.” This attempt at uniformity failed, especially when it came to groups such as Jews and Buddhists. Jews simply did not have a category that was closely analogous to a Catholic or Protestant communicant.

In 1890, the Bureau had differentiated between Reform and Orthodox congregations. Again, different standards of membership presented a challenge. According to Uriah Engelman, Orthodox synagogues had relatively fewer full members and more seat holders. When the Bureau began conducting the decennial Religious Bodies census in 1906, it dropped the distinction between Jew and Orthodox. A census that differentiated among myriad Baptist groups now simply counted Jewish congregations and their members or seat holders.

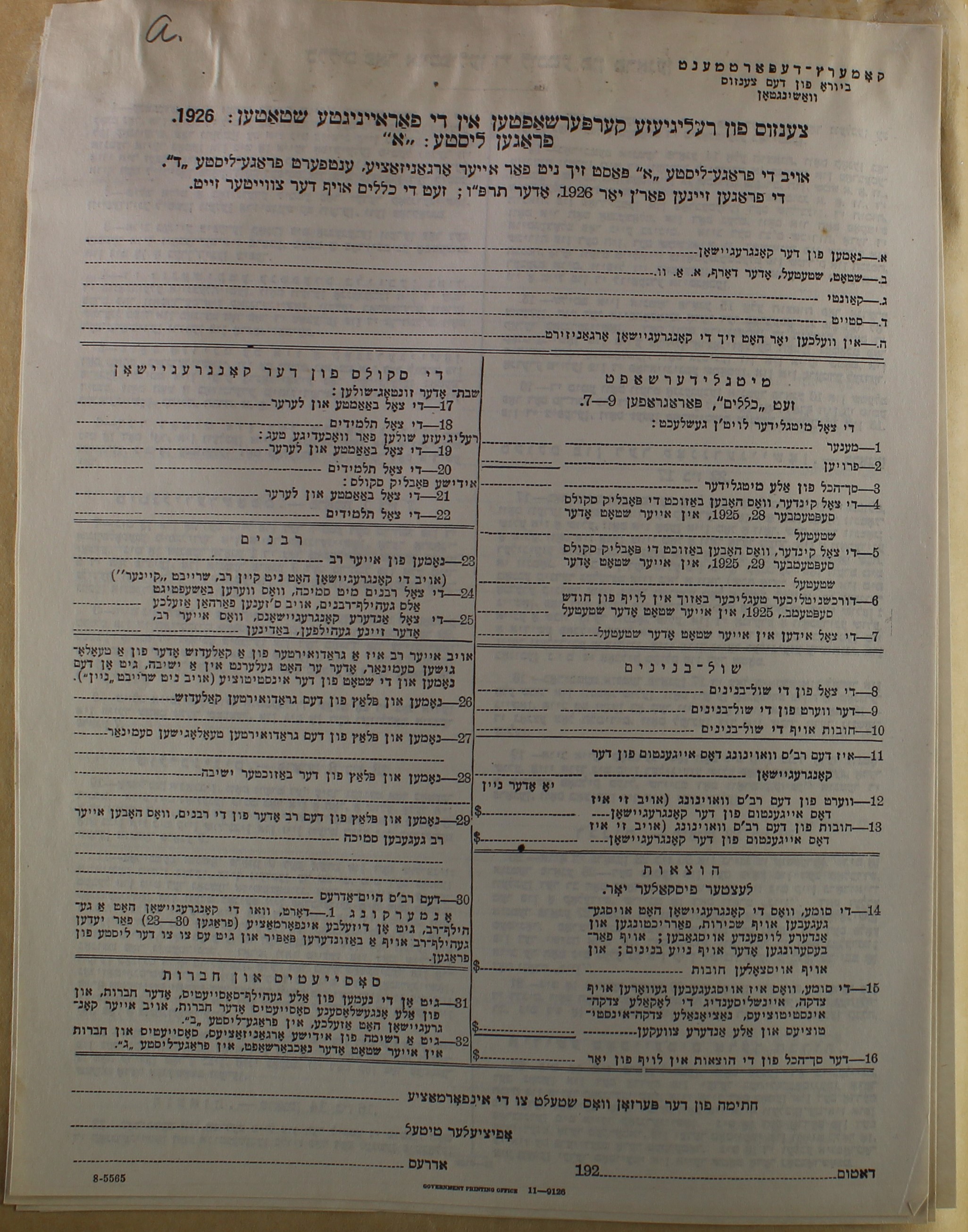

Figure 1. The Hebrew-language congregational schedule prepared by the Bureau.

The Bureau, and those organizations that advised it, struggled with the question of how to enumerate Jewish members. In 1906, the first Religious Bodies census counted as Jewish members only (male) heads of families. In 1916, there was considerable confusion. Some Jewish organizations enumerated heads of families, while others counted seat holders (those who paid for seats but did not have voting privileges). Either of these methods produced statistics that undercounted Jewish participation in religious congregations.

Partly because it regarded the participation of Jewish congregations in the census as unsatisfactory and the Jewish statistics as flawed, the Bureau in 1926 outsourced the counting of Jewish congregations to the American Jewish Committee. The collaboration produced a greatly expanded definition of Jewish membership. “The Jews,” the Bureau reported, “now consider as members all persons of the Jewish faith living in communities in which local congregations are situated.” The expanded definition increased the number of Jews nearly tenfold.

This decision was not reached without some consternation on the part of Bureau officials, who informed the AJC in 1926 that they “would not accept estimates based upon population.” Cyrus Adler and Harry S. Linfield promised the Bureau that they would provide it “with as trustworthy figures on adherents to Judaism as it is possible to secure.” The Bureau appointed Linfield, director of the AJC’s Bureau of Jewish Social Research, as its agent to collect and tabulate Jewish membership for the census.

Even though the Bureau wanted a count of membership, Linfield and the AJC proceeded to count or estimate the entire Jewish population of cities and towns with synagogues or other Jewish organizations. While Linfield did send out and collect membership schedules from Jewish organizations, he decided that the statistics for Jews in major cities significantly undercounted the actual Jewish population. At least for large urban areas, Linfield supplemented data from schedules with estimates based on “statistical formulas.” After its initial expressions of concern, the Bureau decided that it could live with the AJC’s methods.

Linfield had several prominent Jewish critics. Louis Marshall, a prominent New York City lawyer and the AJC’s president, privately mocked Linfield’s work. “If I were a ‘soul-saver’ I would take wings and ascend to heaven,” he commented on the remarkable increase in the country’s Jewish population. “What may we not expect in 1936! ‘The whole unbounded continent’ will then be ours.” Marshall concluded that “of all the lying figures I have ever seen these … are ‘the lyingest.’” Statisticians piled on. “The number of Jews living in a community,” alleged Uriah Engelman, “was arrived at in most cases by methods bordering on guessing.” The Bureau itself recognized that its Jewish statistics remained badly flawed, so flawed that it omitted Jews from its general calculations about religious trends. For instance, given the artificial increase of Jewish members from 1916 to 1926, it made no sense for the Bureau to include Jewish members when calculating the overall growth in religious membership from decade to decade. In several respects, concluded Engelman, “the Jewish statistics of the census of 1926 must be written off as a complete and grievous loss,” one that in his mind “affected adversely the completeness of the entire census.” More recent historians have also noted the deficiencies of the Jewish statistics in the Religious Bodies censuses. In his Synagogue in America, Marc Lee Raphael comments on the “uselessness of the census” when it comes to data about Jewish congregations and their membership.

The deficiencies of the Religious Bodies census respecting Jewish statistics are also a challenge for the American Religious Ecologies project. It is disappointing, to say the least, not to have access to individual schedules for the single biggest non-Christian group in the early twentieth-century United States. At the same time, this challenge also presents us with opportunities. The American Jewish Historical Society holds the extensive papers of Harry S. Linfield, including his research files. Few of those contain information on the 1926 census, but there is extensive information pertaining to his broader statistical tabulations and analyses of Jewish communities. It is likely that these research files, along with the annual American Jewish Yearbook, could help us reconstruct the particular places, membership, and activities of Jewish congregations.

Sources:

American Jewish Committee minutes, American Jewish Committee Archives, New York City.

Engelman, Uriah Zvi, “Jewish Statistics in the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies (1850-1936),” Jewish Social Studies 9 (April 1947): 127-174.

Linfield, Harry S., Statistics of Jews and Jewish Organizations: Historical Review of Ten Censuses (New York: American Jewish Committee, 1939).

Marshall, Louis, to Harry Schneiderman, 11 March 1929, American Jewish Committee Archives.

Raphael, Marc Lee, The Synagogue in America: A Short History (New York: New York University Press, 2011).