Why "religious ecologies"?

While some Americans have lived in rich religious ecologies, surrounded by a plethora of denominational choices, others have lived in places with only one or a few religious options. Using new and existing datasets, American Religious Ecologies documents and maps these environments. How did certain groups come to thrive in particular places, and how were they divided by race and social class? Did cities, towns, and rural areas feature meaningful religious pluralism and diversity, or were they dominated by some particular religious group? How did the balance of diversity and dominance vary across space and time?

While scholars have often studied the religious ecology of a particular city or place, studying how those ecologies varied across the nation has been difficult because of the lack of data that is available. The American Religious Ecologies project is creating new datasets from historical sources and new ways of visualizing them so that we can better understand the history of American religion.

Follow the Project

New datasets and maps for American religious history

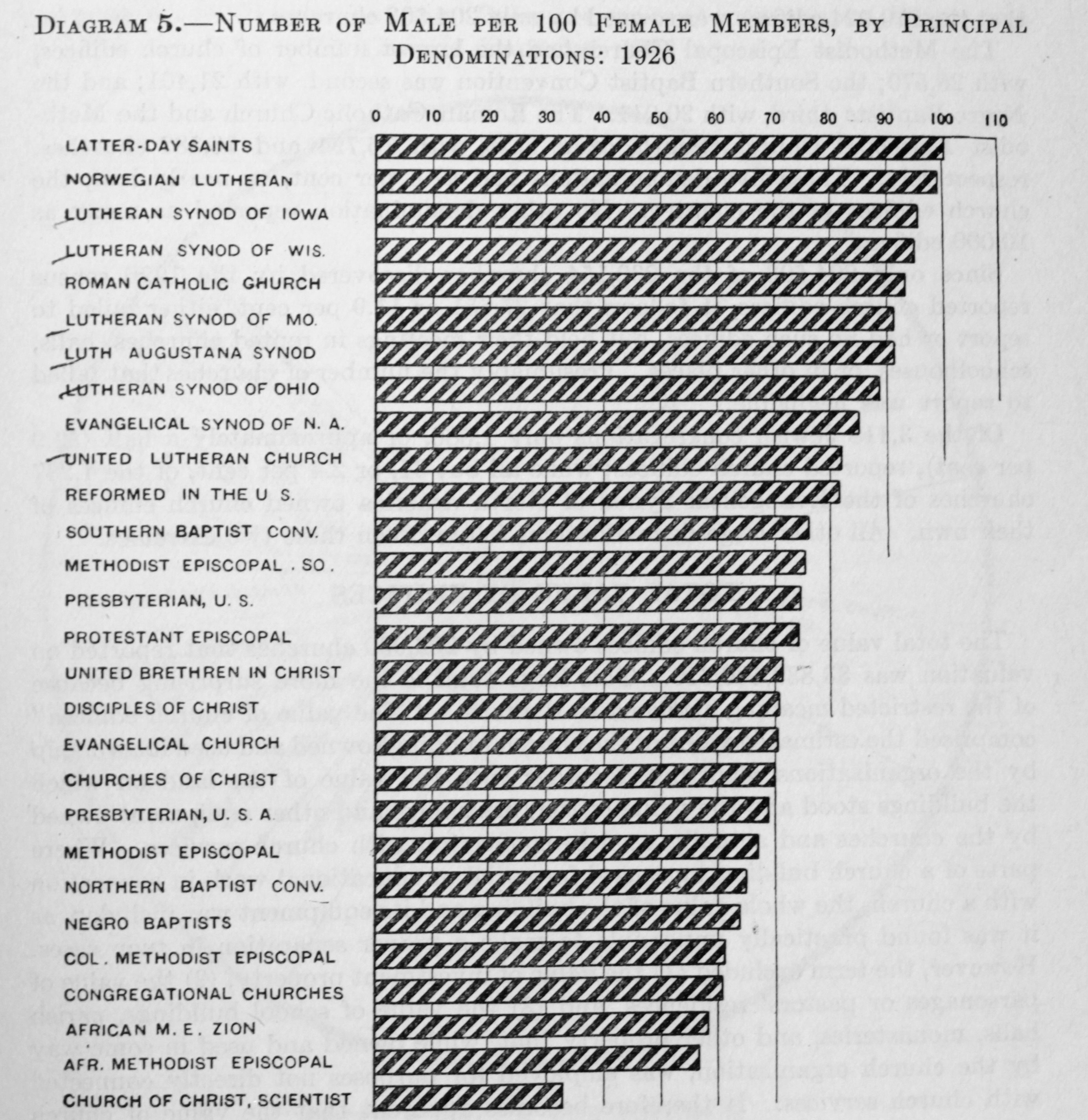

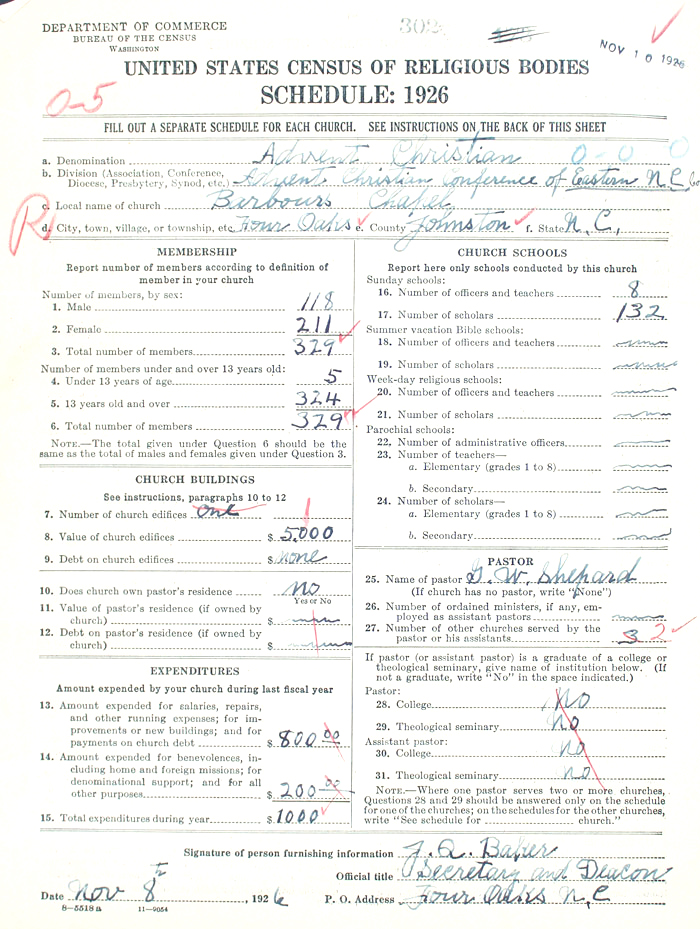

The American Religious Ecologies project seeks to understand how congregations from different religious traditions related to one another by creating and visualizing new datasets. Datasets, maps, and other visualizations are one way of approaching the questions that we have asked, because they allow us to work at multiple scales, seeing how individual congregations fit into a local religious ecologies and then how local ecologies differed across space. In addition to making the schedules of the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies available on this website as photos of the records, we are transcribing the census schedules as well as parts of the published census reports into datasets. We have also started to gather data about American religion from other historical sources, such as collections of denominational yearbooks. As we create these datasets and map them, we hope to create a rich depiction of how congregations related to one another in their local environments.

See our visualizations of American religious history.Digitizing the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies

There are few comprehensive and detailed datasets for studying American religion before the middle of the twentieth century, except the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies. At the start of the twentieth century, Congress authorized the U.S. Census Bureau to survey the nation’s “religious bodies.” For five decades, the Bureau partnered with religious organizations to identify hundreds of thousands of individual congregations across the country, asking them to report on their membership by sex and age, as well as on their educational programs, buildings, budget, and clergy. The vast majority of the several hundred denominations the Census Bureau identified were Christian, but Jews, Bahá’ís, and Theosophists, and other non-Christian groups participated as well.

The hefty volumes of data published from these Religious Bodies censuses let us see the national picture, but the individual schedules reveal a far richer picture of congregational diversity at the local level. Congress authorized the destruction of the schedules from some of the censuses, and others have been lost. Only the schedules from the 1926 census still survive. These schedules, however, are a treasure trove of congregation- and place-specific data and contribute to a fuller and more vivid depiction of the religious landscape of the early twentieth-century United States. With the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Religious Ecologies project is digitizing the 232,154 schedules from the 1926 census.

Browse schedules from the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies.