Female Pastors in the 1926 Census Schedules

The 230,000 census schedules from the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies give scholars a plethora of demographic information regarding religious congregations in the early twentieth century. The digitized schedules allows scholars to study the denominational affiliation, place, size of the congregation, and organizational finances. However, few people’s names appear on the census forms. Usually only the pastor’s name is listed, and sometimes that of an assistant pastor. Sometimes a clerk or a secretary of the church signed the bottom, stating that they filled out the form, but often a pastor completed this as well. This means at most there are only three people’s names represented in the form. Even with multiple names, however, the identity of the people listed in the schedules remain hidden, with initials often used instead of full names.

Throughout thousands of digitized census schedules from 1926, women’s names rarely appear. The most common occurrence for a woman’s name to be on the schedule is at the bottom, since women often acted as secretaries and clerks and filled out the schedule for their congregation. Yet, there are instances of women who were pastors of their congregation, giving insight into female preachers and other religious leaders across the nation in the early twentieth century. The churches headed by female pastors varied in size, denomination, and location, but the census shows female pastors represented in leadership positions across the nation.

Though women preached before the twentieth century, even if not all who did so used the word “preacher” or a similar designation for themselves, they rarely headed their own church. The presence of women as religious leaders, using titles like “Elect” or “Reverend” at times, allows us to recognize a small, but present, shift towards women in formalized leadership positions.

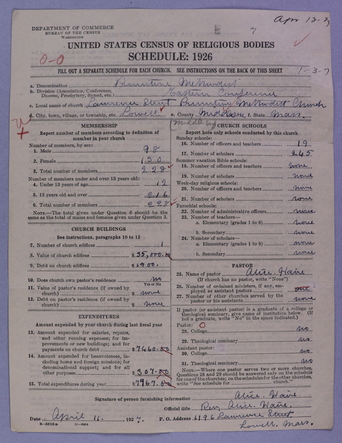

Women represented in the 1926 Census include Nettie Rowe, pastor at Mehida Pentecostal Church in Canaan, New Hampshire; Mrs. Almira A. Nate of an Adventist Christian Church in South Berwick, Maine; Retha Glover of an Adventist Christian Church in Oxford, Maine; Mrs. Susie W. Davis of Crouseville A.C. Church and Dunntown Advent Christian Church in Crouseville and Wade, Maine; Mrs. Olive O. Nolan of Union Church in Center Haverhill, New Hampshire; Lottie M. Smith of Beechwood Community Church in Rochester, New York; Mrs. Ida Manville of Willow Grove in Mt. Liberty, Ohio; Lettie L. Glazier of Lisbon Advent Christian Church in Lisbon, New Hampshire; Elect Ella DeShields of Church of God in Christ in Robertsville, Mississippi; and Rev. Alice Haire of Lawrence Street Primitive Methodist Church in Lowell, Massachusetts. Elect Ella DeShields ran the Church of God in Christ, which had twenty-two members with ten men and twelve women. There was one church building, valued at $700, showing that DeShields ran a small congregation. Rev. Alice Haire, on the other hand, was in charge of a rather large church in Lowell, with 228 congregants, 130 women and 98 men, and a church school with 245 students. The value of the church building was placed at $35,000, and with the relative cost of the church and the number of congregants, outlining the financial affluence of the large congregation. An image of the schedule from the Census appears below.

Figure 1. Schedule of the Lawrence Street Primitive Methodist Church in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Alice Haire was the pastor.

The possibility of other female preachers and religious leaders in the Census is strong; especially considering the number of pastors identified only by their initials, leaving ambiguity to their gender. The Census also does not document the other leadership positions women could have held in many congregations outside of the role of pastor. Though American Religious Ecologies is still in the process of digitizing schedules, the denominations we have digitized often had more acceptance of women being involved in church leadership and preaching; so these women most likely represent a good portion of women in the census.

What can we learn from these women listed above? We learn that married women still sometimes headed a church, probably with the support of their husband and family as they continued their calling. We see that some pastors refused to shy away from titles such as Reverend or Elect, taking the honorific given to religious leaders. We see that female pastors were not concentrated in one part of the country, instead being in southern and northern states, as represented in this non-exhaustive list. By using census data, we can also see that women headed churches both big and small, sometimes with a dozen or so congregants, and sometimes with hundreds. We also get an inside look into finances of the church, with information regarding church buildings and pastor residences to study the financial influence of churches that had female pastors. As the census schedules continue to get digitized, we can compare the number of female pastors in different denominations to see which denominations were more open to women in leadership roles.

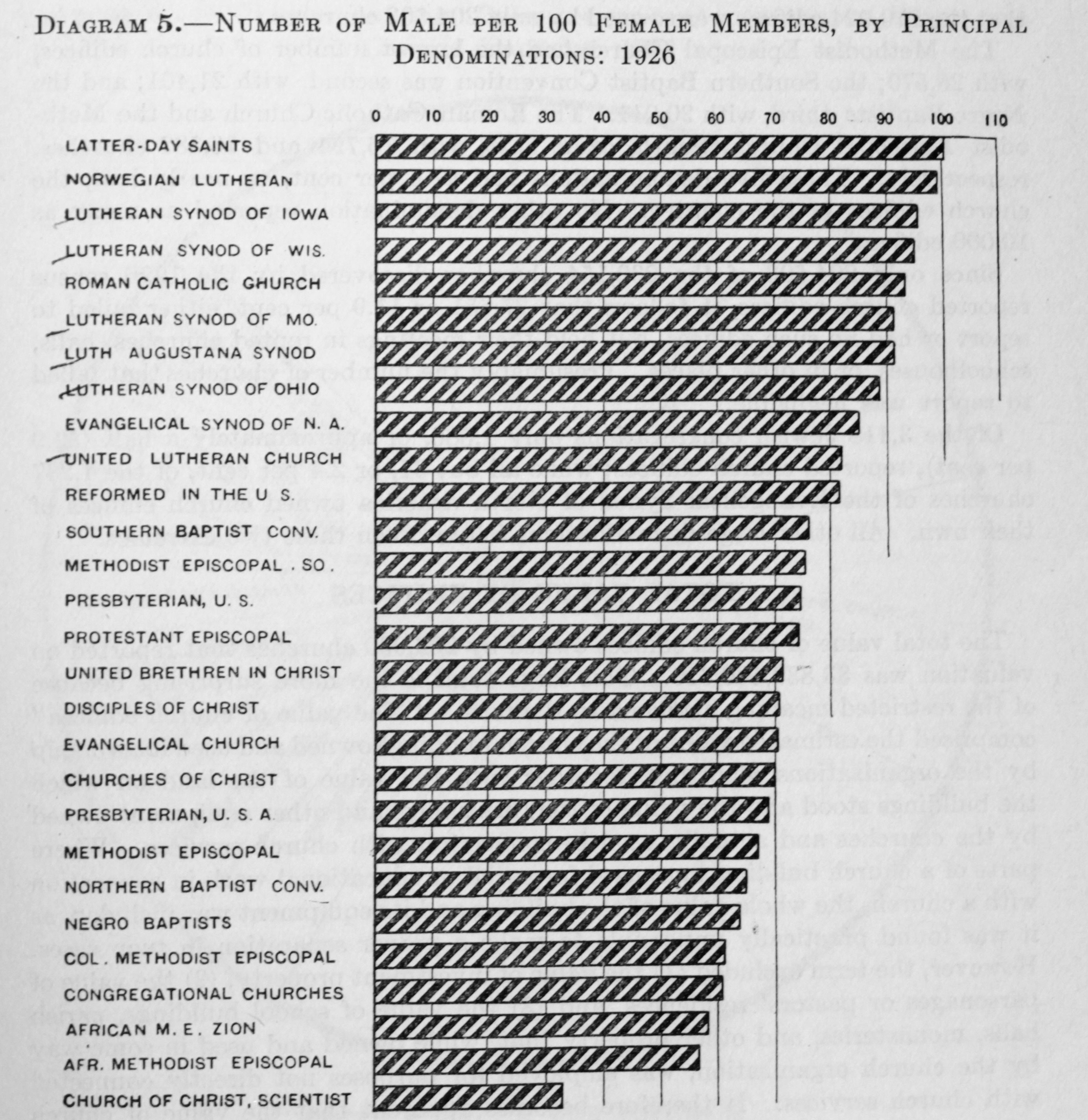

The underwhelming numbers of women as pastors, ministers, preachers, or other leaders do not represent the bodies in the pews. In many congregations, women vastly outnumber the men as members, and rarely are the numbers close to equal or have men outnumber women. Below is a table created from 1926 census data showing that many denominations had more women than men, a difference on average of five women per four men. These statistics show the lack of representation of the female members of the churches in leadership roles of churches poses questions about gender and religion in the United States almost a century ago; a question that still resonates today across denominations.

Figure 2. A visualization of the ratio of women to men in denominaitons created by the Census Bureau.

For further reading on the subject of female pastors and women in church leadership roles, Catherine Brekus’ Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 is a pivotal work thinking about female preachers, though its focus is the late 18th and early 19th century. More contemporary resources include Gender and Pentecostal Revivalism: Making a Female Ministry in the Early Twentieth Century by Leah Payne. For an online accessible article that focuses on European women, look to Musee Protestant’s “Woman Pastors from 1900 to 1960.”