How the Religious Bodies Census Changed Its Questions Over Time

The 1926 U.S. Census of Religious Bodies and the surviving schedules for over 200,000 congregations provide the opportunity to use data to answer questions about religion in the early twentieth century. The possibilities of working with this data mean that scholars must consider how those at the Census Bureau understood religion and religious organizations, how these considerations created the schedules, and what information was collected by the Bureau.

How did the Census Bureau think about religion? Of course, we have covered this a good deal in other blog posts, such as Lincoln Mullen’s “What can you learn from a census schedule?,” which looks at the schedules as a whole, or John Turner’s post “‘Negro Baptists’ in the US Census of Religious Bodies,” a case study about the denominational designation and race. Even my post, “Female Pastors in the 1926 Census Schedules,” shows that scholars can use the schedules to ask questions not explicitly related to the data, such as questions about gender. But another way to approach the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies is to consider the changes to the questions the Bureau asked during different census years.

Our earlier post discusses how the Census Bureau started (and stopped) asking questions about religion. To summarize, the Census Bureau started asking questions about churches and denominations in 1850, expanded those questions into a separate Religious Bodies census in 1906, and then stopped gathering this information after 1946.

Though we no longer have the schedules from the 1906, 1916, and 1936 censuses, the published reports from the Bureau tell us about the questions asked on the schedules sent out to religious organizations. With this information, we can consider the changes in what the Bureau asked, and what information they found important in later decades. For example, in the 1906 census, the Bureau asked organizations about the number of people they could seat and about the languages used for services. Later schedules asked neither question.

The censuses from 1906 to 1936 each asked different questions about the leadership of religious congregations. The inquiries about the religious leaders often provide the only name on the schedule, providing a human touch to otherwise numerical data. Therefore, the questions regarding ministers and clergy are helpful windows into individual congregations.

In 1906, the Bureau asked for little information about the ministers. There was only one question on the schedule. The field simply asked for “Ministers (number of; salary)” and did not request any names of ministers. 1 This question, however, was a new addition from the earlier questions from 1850–1890, just like other questions that expanded the inquiry of the Religious Census. The published reports focused on the ratio of ministers to organizations, of ministers to congregants, and on the salaries of ministers.

In 1916, the Bureau included a Schedule for Ministers, sent to all clergy whose contact information could be found. This schedule asked for some information similar to questions included in the 1926 Census, though it was separated out. As stated in the published reports, “the statistics of ministers were gathered by sending a card schedule to the ministers direct. The lists of ministers, with addresses, were obtained in most cases, as in the case of the churches, from various denominational publications.”2

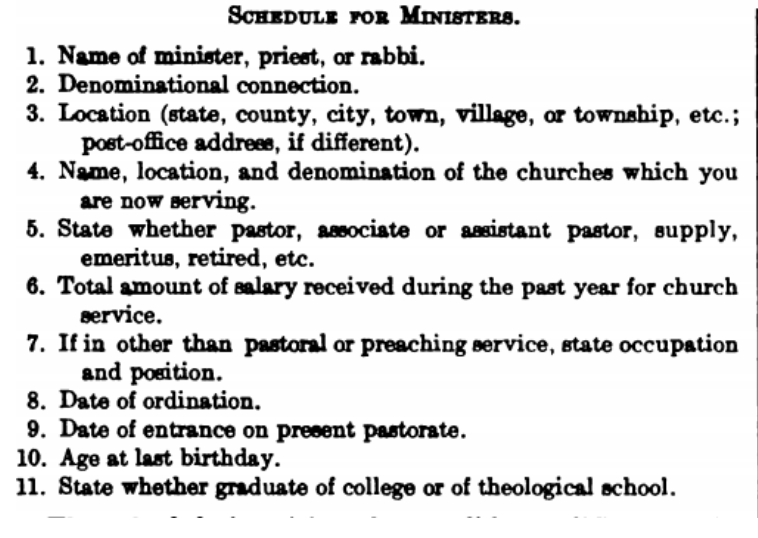

Figure 1. List of questions included on the Schedule for Ministers, Religious Bodies 1916, 1:12.

The 1916 Census explicitly asked for the name of the “minister, priest, or rabbi” who led the congregation, any other churches they served, their salary, if they had any other occupation, date of ordination, age, and if they graduated from college or theological school.

By including a separate schedule for ministers and inquiring personal information about the leadership of the church, the Bureau gathered a large amount of data and emphasized the importance of leadership in the reports. Yet, the method of separating out the schedules for ministers from the overall schedule proved to have its faults. As the published reports stated,

The number of schedules received from ministers in response to the inquiries sent out fell very far short of the number of ministers reported as on the rolls of the denominations. For this there were several reasons. Some of the denominations failed to give the addresses of all ministers included on their rolls. … Changes were constantly taking place, by death or removal, so that the schedules failed to reach the ministers. In other cases the minister’s schedule was confused with the church schedule, and in a certain percentage of cases through sickness, forgetfulness, or other cause, no reply was made. 3

The reports give a 52.6% rate of return on the number of schedules for ministers. The failures of the separate ministers’ schedule likely led to the removal of the second schedule and the consolidation of questions regarding ministers in 1926.

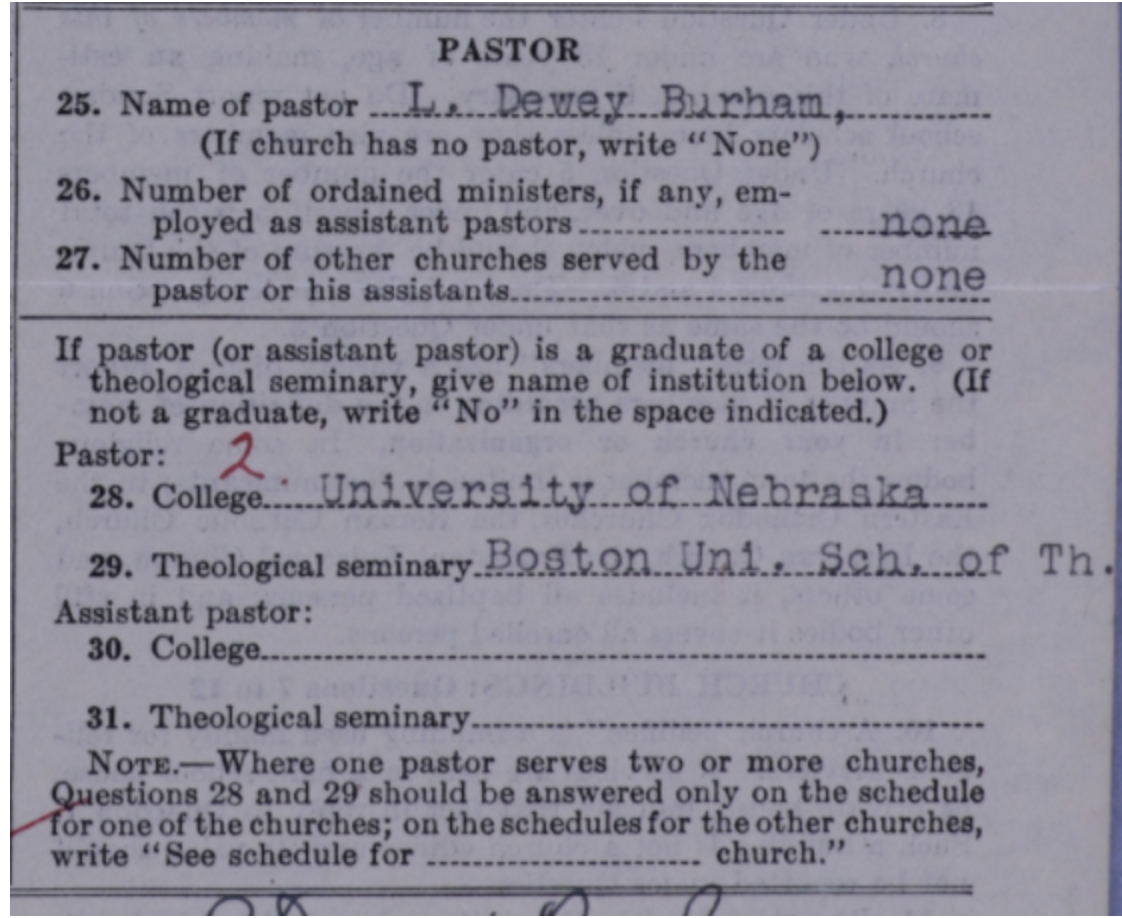

Figure 2. The 1926 questions as answered by the pastor of Bedford Presbyterian Church in Bedford, New Hampshire.

The 1926 census only asked if there were a pastor and/or assistant pastors (instead of ministers), and if so, their names and education, as well as if they served any other church. The schedules have no questions related to the salary, unlike the prior two censuses.

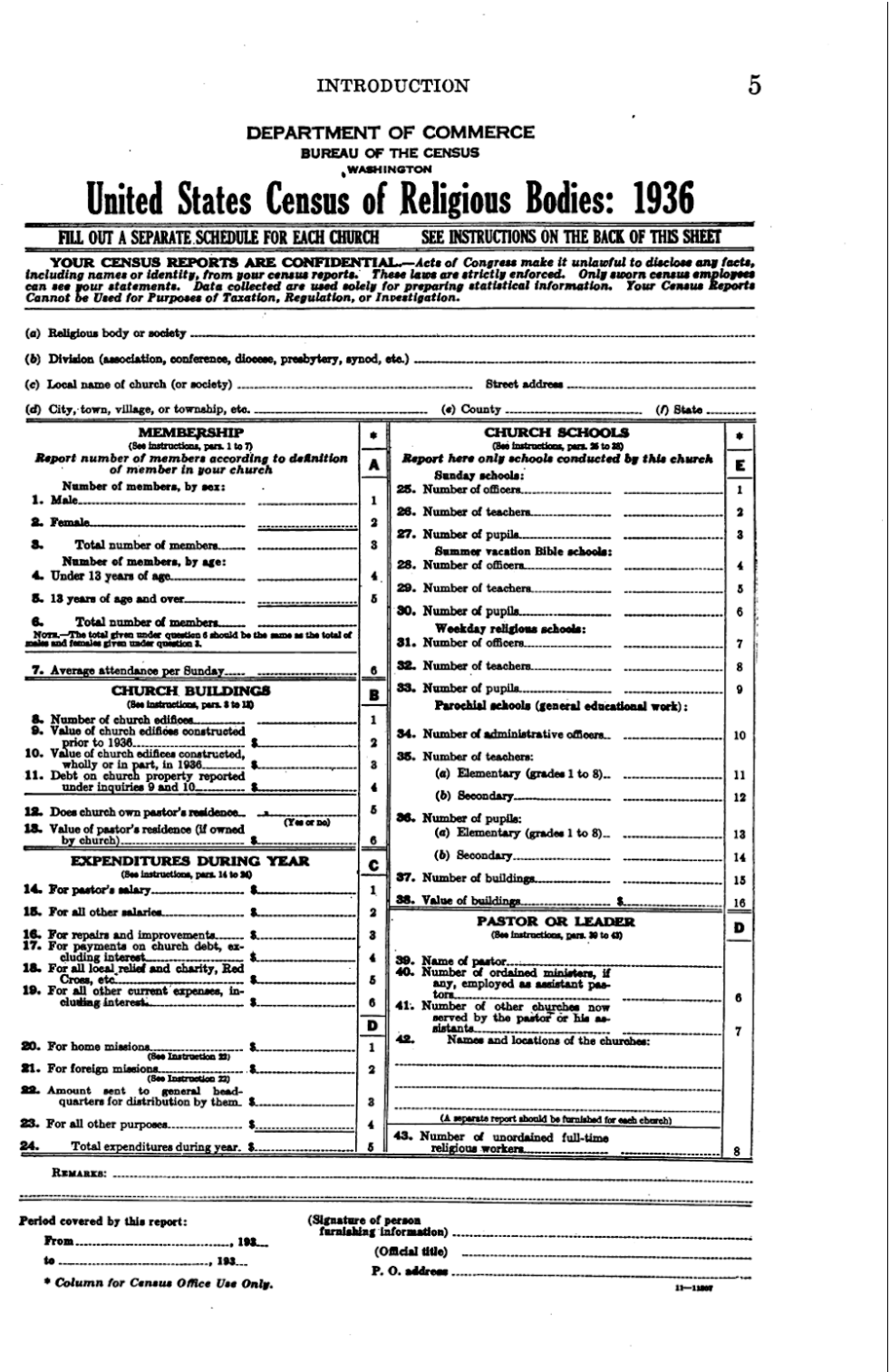

The 1936 census looked similar to the 1926 one, with some important distinctions. First, the 1936 schedule entitled the section “PASTOR OR LEADER,” using more inclusive language for non-Christian congregations. Second, the census asked for the locations of the other churches that the pastor served, if there were any. Third, the schedule asked for the “Number of unordained full-time religious workers.” This last question implies that the Bureau began to recognize the importance of church leadership outside of the role of minister, an important insight, given how much labor goes into running a congregation.

Figure 3. The sample schedule form from the 1936 U.S. Census of Religious Bodies, Religious Bodies: 1936 1:5

The changing questions about ministers and church leadership provide an example of how the Census Bureau refined its survey with each successive decennial census. Bureau officials had to decide which information was most valuable to the public and which information was feasible to collect. For example, salary ceased to become a question, but education remained even when the number of questions related to ministers was cut. Therefore, the questions related to the leadership of the churches and religious organizations provide a way of understanding how those working with the Bureau thought about religious data, how they decided what questions were important or not, and how they worked with hundreds of thousands of organizations.