“Negro Baptists” in the U.S. Census of Religious Bodies

In 1926, the U.S. Census Bureau added “Negro Baptist” to the list of denominations included in its survey. The new term replaced the “National Baptist Convention,” used in the 1906 and 1916 decennial surveys of American congregations. Why the change? The National Baptist Convention had not changed its name. Moreover, while there were several African American Baptist denominations, there was not one named “Negro Baptist.” Why, then, did the Census Bureau begin using that term? What presumptions about race guided the Bureau’s survey of religion?

In 1890, the U.S. Census Office (predecessor of the permanent Census Bureau) began tracking what it referred to as “the colored element in church statistics.” In its decennial population census, the Census Office used the term “colored” to refer to all peoples it categorized as non-white, including “Indians, Chinese, and Japanese, as well as negroes and persons of negro descent.” For its work on “church statistics,” however, the Census Office approached race in a binary way, using it to “designate negroes and those of negro descent.”1

The Bureau maintained this approach once it began the decennial Religious Bodies census in 1906. The Bureau both tracked African American denominations and asked other denominations to classify predominantly African American congregations within their bounds. While it asked individual congregations to count male and female members, and it asked congregations to count members under 13 years of age, it did not ask individual congregations to count white or black members. By contrast, many denominations such as the Methodists did keep track of the race of their members.

The Bureau then compiled statistics on African American churches, concluding that they were, on average, smaller and more rural than other churches. The Bureau also noted that “the excess of females among the memberships of the Negro churches was very pronounced.” Across the board, American churches reported 79.7 men for every 100 female members, whereas the figure was 61.9 for African American churches. The Bureau’s language of “excess” reflects a widespread apprehension among American Christians that churches were failing to attract men in sufficient numbers.

An examination of Baptists in the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies illustrates the significance of race and racial categories in the Bureau’s work. In that decennial survey, the Bureau gathered data on 18 Baptist “bodies.” The Bureau counted General Six-Principle Baptists, Separate Baptists, Duck River Baptists, and even the Two-seed-in-the-Spirit Predestinarian Baptists (per the Bureau’s summary, the latter emphasized “specific election of the seed of God to salvation and the seed of Satan to reprobation.”).2

As the Bureau noted, however, most Baptist churches “are ordinarily spoken of as ‘Northern,’ ‘Southern,’ and ‘Colored.’”3 Correspondingly, the three largest Baptist denominations in the 1926 Census were the Southern Baptist Convention, the Northern Baptist Convention, and the Negro Baptists. The SBC and the Negro Baptists were, respectively, the fourth and fifth largest “bodies” or “denominations” in the Bureau’s 1926 survey.

Baptists alone provide ample evidence for the centrality of race in the history of American Christianity. In 1845, white southern defenders of slavery separated from their northern counterparts to form the Southern Baptist Convention. Northern Baptists remained more loosely organized until they formed the Northern Baptist Convention in 1907. Also, in the wake of the Civil War, many African American Baptists in the South left white-controlled denominations and conventions to form their own churches. In its 1926 Census of Religious Bodies, the Bureau counted two such movements: the Colored Primitive Baptists; and the United American Freewill Baptist Church (Colored).

The Bureau discussed this history of race and religion with naive insouciance. “During slave times,” it explained, “the colored Primitive Baptists had full membership in the white churches, although seats were arranged for them in a separate part of the house.” It is hard to imagine that all of the African American Primitive Baptists in question felt that their white counterparts accepted them as “full members.” They might have also resented the Bureau’s description of their ecclesiastical direction after the Civil War: “After the Negroes were freed, many of them desiring to be set apart into churches of their own, the white Primitive Baptists granted them letters certifying that they were in full fellowship and good standing; white preachers … set them up in proper order, throughout the South; and thus, gradually, the colored Primitive Baptists became a separate denomination.” One suspects that African Americans among the Primitive Baptists were far more active participants in the securing of their freedom and religious self-determination.4

What about the designation Negro Baptist? It is a curious term. As the Bureau’s own summary made clear, “colored Baptists” and “Negro Baptists” were commonly used terms in the early twentieth century. There was, however, no “Negro Baptist” denomination or convention. And there was no “white Baptist” designation. As it turns out, the Bureau did not use the term “Negro Baptist” in the 1906 or 1916 Religious Bodies censuses. It was a new creation for the 1926 census.

Every ten years, the Bureau reassessed its list of denominations. The largest Black Baptist denomination in the United States was, by far, the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A. The Bureau counted it as a separate denomination in 1916, but it elected not to do so a decade later. The explanation was that there had been several minor schisms within the National Baptist Convention, among them a separation that led to the creation of the Lott-Carey Convention for Foreign Missions. Perhaps because these developments confused the Bureau and were in flux, the Bureau chose to lump a variety of Black Baptist groups into the less specific “Negro Baptist” term.

One other issue added to the complexity of the “Negro Baptist” designation. The Bureau also counted “Negro congregations” within predominently white denominations. For instance, in 1926 it counted nearly 4,000 such congregations within the Methodist Episcopal Church, but also more than four hundred within both the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. and the Disciples in Christ. As part of its creation of the “Negro Baptist” designation, in 1926 the Bureau counted “colored Baptist churches that were formerly included in the Northern Baptist Convention.”5

To summarize so far, unlike “Presbyterian Church U.S.A.” or “Southern Baptist Convention,” the term Negro Baptist in the 1926 U.S. Census of Religious Bodies does not signify an actual denomination, convention, or church. Rather, it’s a quasi-denominational term that the Census Bureau found useful to bring together a large number of African American Baptist congregations.

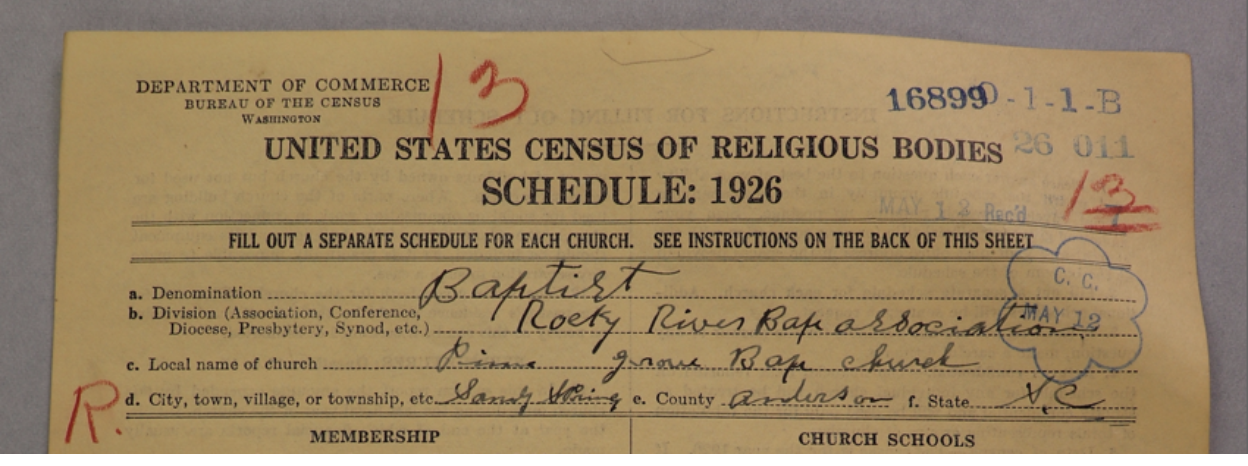

Although the Bureau described African American churches in ways that were both racist and not fully accurate, there were some pragmatic reasons for the Negro Baptist designation. As a general rule, Baptist churches were hard to count and categorize. See, for instance, this schedule from the Piney Grove Baptist Church in Sandy Springs, South Carolina (figure 1).

Figure 1. Schedule from the Piney Grove Baptist Church in Sandy Springs, South Carolina.

As was common, the congregation identified its denomination simply as “Baptist” and its division as the “Rocky River Baptist Association.” For many congregations, the link to state and regional conventions and associations mattered more than a connection to any national movement. In its published report on the 1916 Religious Bodies census, the Bureau stated that “special effort was made to secure complete lists of Negro churches, which were difficult to obtain, on account of the lack of any inclusive ecclesiastical organization.”6

In our examination of the individual Negro Baptist schedules, we have uncovered traces of the Bureau’s internal work. As a general rule, the Bureau assigned a three-digit code to each denomination. The Seventh Day Adventists are 0-0-1, the Northern Baptists are 0-0-9, the Southern Baptists are 0-1-0, and so forth. The Negro Baptists form the one known exception to this rule. Most of the Negro Baptist schedules are marked 0-1-1-A, but we found some stamped 0-1-1-B (see the above Piney Grove Baptist Church schedule), some that are 0-0-1 (without an A or a B), some marked 0-0-9 (Northern Baptist), and some without any denominational code.

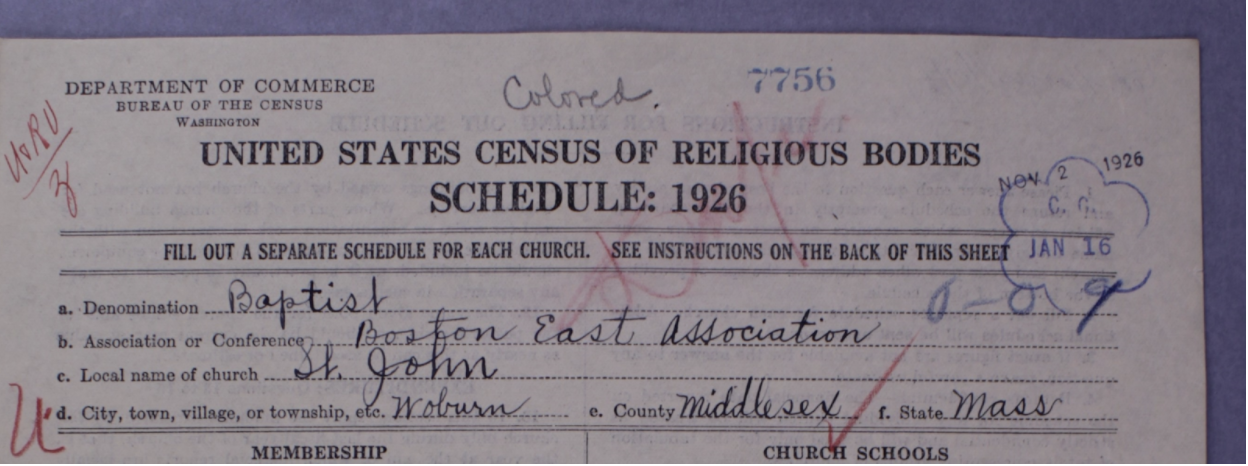

See, for example, this schedule from St. John’s Baptist Church in Woburn, Massachusetts, founded in 1886 and still active today. Initially, the Bureau categorized the congregation as belonging to the Northern Baptist Convention. Either Northern Baptist or Bureau officials, however, wrote “Colored” at the top of the schedule, and Bureau officials recategorized it as “Negro Baptist.”

Figure 2. Schedule from St. John’s Baptist Church in Woburn, Massachusetts. The Bureau wrote ‘Colored’ at the top of the schedule.

Once we have all of the Negro Baptist schedules digitized and processed, it might be possible for us to reverse engineer the Bureau’s work, at least in terms of separating the congregations into their National Baptist, Northern Baptist, and Lott-Carey affiliations.

Bureau officials discussed the organizational shortcomings of African American denominations in disparaging ways. There were similar issues involved in categorizing and counting white Baptist churches, but the Bureau repeatedly stressed the challenges of surveying African American churches.

Nevertheless, other factors—not mentioned by the Bureau in connection with the Religious Bodies census—also impeded the Bureau’s ability to count African American churches. The Bureau’s decennial Religious Bodies census sought to produce a snapshot of the American religious landscape, but snapshots necessarily do a poor job of documenting the movement of peoples. This observation does not pertain only to African American churches. As of the 1920s, Americans continued to leave rural areas for cities in large numbers (one reason the Bureau categorized each congregation as either urban or rural). But it is worth considering that the 1926 Religious Bodies census took place precisely when many African Americans were leaving the South and moving to northern cities such as Chicago. The Great Migration reshaped and sometimes relocated African American congregations.

Categorizing and counting religion are not simple matters. When it came to African American religion, the Bureau began its work with two presuppositions: 1) it was worthwhile to compile statistics on “colored” / “Negro” churches but not on either Native American or Asian American religious bodies; 2) the task of counting African American churches posed distinctive challenges. While the entire Religious Bodies census reflects the power of the state to count (and determine who counted), the creation of a “Negro Baptist” designation reflects the power of the state to classify. For its own purposes, the Bureau chose to classify African American churches in ways that both reflected and departed from the self-understanding of the people who belonged to them.

Henry K. Carroll, Report on Statistics of Churches in the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894), xixv. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1926 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1930), 2:219. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1926, 2:79. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1926, 2:213. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1926, 2:82. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1916 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920), 129. ↩︎