Schedule Spotlight: the Amana Society

This month’s spotlight schedule comes from a communitarian Pietist sect in Iowa. The Amana Society, or Amana Colonies, had seven villages, each coinciding with one of the seven organizations listed on the master schedule: Middle Amana, Amana, South Amana, Homestead, West Amana, High Amana, and East Amana.

![Figure 1. General Store and Office for the Amana Society located in Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Amana Colonies General Store & Offices, State Route 220, Amana, Iowa County, IA,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/ia0012/]](/blog-img/amana-general-store.jpeg)

Figure 1. General Store and Office for the Amana Society located in Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Amana Colonies General Store & Offices, State Route 220, Amana, Iowa County, IA,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/ia0012/]

The Amana Society had origins in eighteenth-century Germany. Eberhard L. Gruber and Johann F. Rock founded the precursor to the communitarian society. Rock and Gruber taught that God spoke through individuals, called ‘instruments,’ and the group became known as the Community of True Inspiration. he adherents of the Community of True Inspiration were persecuted byboth the German State and the Lutheran Church. The group, then led by Christian Metz, decided to leave Germany for the United States in 1843. About 800 members first settled in New York, near Buffalo, on 5,000 acres of formerly Seneca land. By 1850, the group strengthened their commitment to communal living by inscribing it in their constitution, and they named themselves The Ebenezer Society. As the group grew larger, they moved to Iowa in 1855 and incorporated as a business under Iowa law in 1859. They chose the name “Amana” for six villages that they established. The name Amana comes from a mountain named in the Bible in Song of Solomon 4:8, and means to stay firm or constant. The seventh village, Homestead, was formed in 1861. Each village had houses, a church, school, bakery, wine-cellar, dairy, post office, saw mill, and general store. Elders governed the village, and no one earned wages. Early on, the Amana Society discouraged both marriage and childbearing, but later their views liberalized. Communal dining was encouraged, but more common early on; over time, married couples ate together more often in their house.1

During the Great Depression, the Amana Society changed the way of life in the villages. In 1932, instead of communal living and a prohibition on wage labor, private enterprise was accepted by creating the Amana Society, Inc. This corporation managed the land, the mills, and any larger enterprises and allowed the residents to share the profits. Those profits allowed the church to be maintained. In 1965, the Amana villages became a National Historic Landmark and are now tourist destinations.2

According the Amana Society schedule, in 1926, the Amana Society’s seven villages had a population of 1,385, which included 297 children under the age of 13. There were 640 male members and 745 female members, aligning with the common trend of more women as members in most denominations. Each village had its own church, but no separate church or parochial schools existed.

![Figure 3. The Main Meetinghouse in Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Main Meetinghouse, State Route 220, Vicinity, Amana, Iowa County, IA,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/ia0010/]](/blog-img/amana-meetinghouse.jpeg)

Figure 3. The Main Meetinghouse in Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Main Meetinghouse, State Route 220, Vicinity, Amana, Iowa County, IA,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/ia0010/]

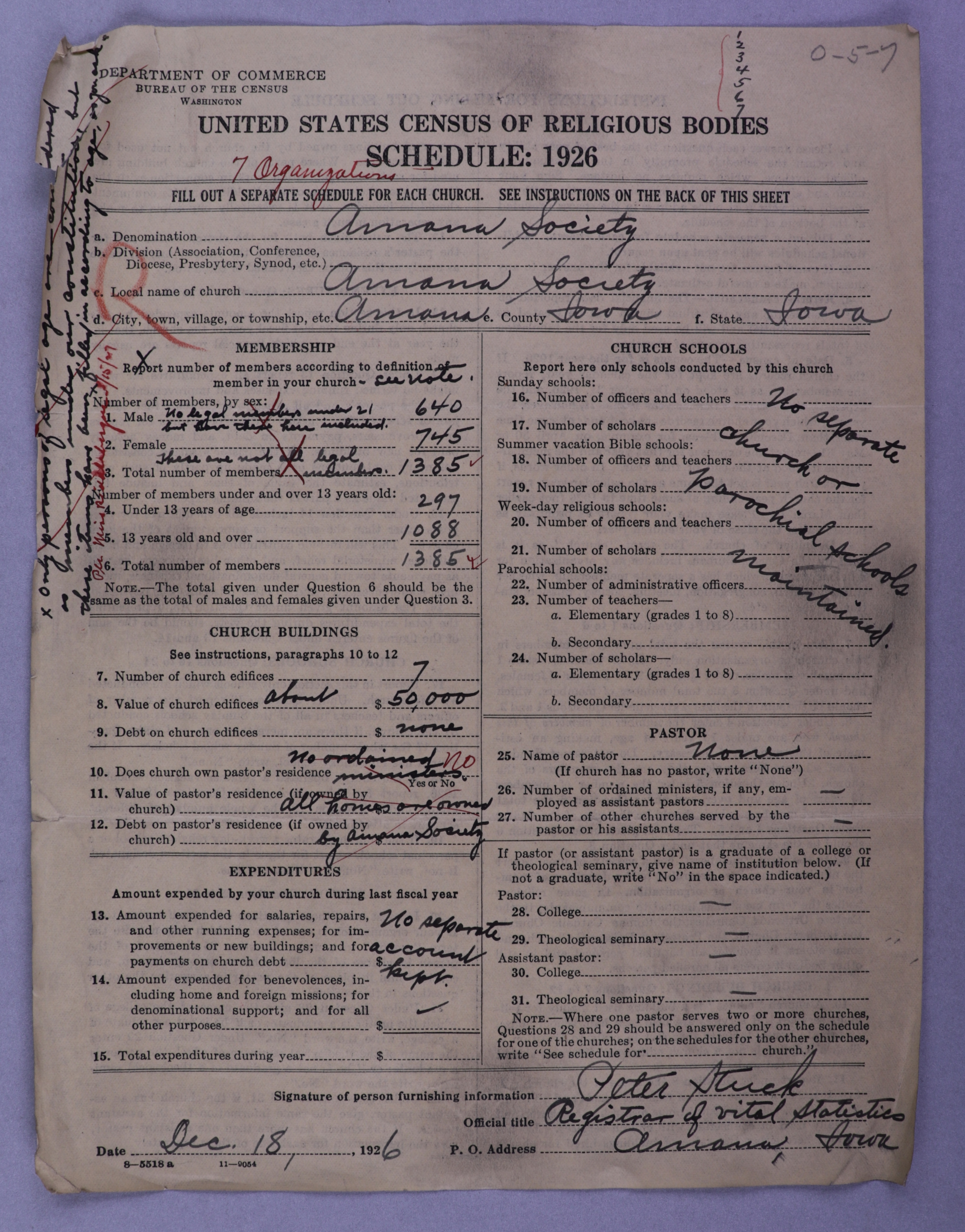

The person who filled out the schedule detailing the seven Amana Society villages left multiple notes in the margins that gave more information about the communal living. The schedule was filled out and signed by Peter Stuck, who listed his official title as “Registrar of Vital Statistics.” As the Amana Society had no official ministers, Stuck was likely chosen to fill out the form based on his role related to statistics. Stuck’s choice to include information that the Bureau did not specifically ask for demonstrated that the Amana Society were both a unique religious community, but that they were also committed to giving information about what was important to them. The Bureau crossed out the notes with large red Xs, marking that they were not interested in the information about housing, membership status, or preachers. However, one hundred years later, the marginalia are some of the more interesting parts of the Amana schedule.

The largest note is on the left side of the schedule near the membership fields. The note reads “Only persons of legal age are considered as members under our constitution, but these items have been filled in according to age, as you ask.” The reference to the Amana constitution helps explain the other notes related to the membership fields; “No legal members under 21,” but they included the count of all community members for both the number of male and female members, and those under and over the age of thirteen, and not just ‘legal members’ according to the Amana constitution. The inclusion of community members and not just those fully affiliated with the church was an important detail that demonstrates that the Amana Society existed more as a community than simply a church with services one day a week. Those in the Amana Society focused on blending their everyday lives with their religious practices. Another facet of the communal living in the Amana Society is shown by the notes included on the schedule. For the section related to the pastor’s house, the note next to the field mentioned that there were no ordained pastors. However, “all homes [were] owned by the Amana Society” is written next to the fields, though once again crossed out in red by the Census Bureau. This again demonstrates how intertwined the infrastructure of the village was with the religious organization and communal living. Interestingly, the Society owning all the houses in the villages meant that even those who were not legal members of the society lived in community-owned houses.

The Bureau did not cross out other notes on the schedule, including one by the expenditures field and one by the fields related to church schools. However, the inclusion of extra information on the schedule, and the decision by the Bureau to cross out some of that information, demonstrates the systematic nature of data collection and how that method can obscur details about denominations and specific congregations. Also noteworthy is that congregations and denominations often highlighted what was important to them, even if the Bureau did not ask. We previously wrote about this in our “American Rescue Workers” blog post that discussed the denomination adding pieces of paper with data about their mission work to the individual schedules. Though the Amana Society additions are of a smaller scale, they similarly demonstrate that different groups emphasized and added extraneous information, such as legal membership status and communal home ownership.

![Figure 4. Barns in Middle Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Barns in Middle Amana, one of the Amana Colonies, seven villages in Iowa County, Iowa,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016630631/]](/blog-img/barns-middle-amana.jpg)

Figure 4. Barns in Middle Amana, Iowa. [Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, “Barns in Middle Amana, one of the Amana Colonies, seven villages in Iowa County, Iowa,” after 1933, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016630631/]

“History of the Seven Villages,” Amana Colonies, https://amanacolonies.com/visitors-guide/history-of-the-seven-villages/ Accessed 23 June 2022; Catherine A. Paul, “Amana Colonies: A Utopian Community,” Social Welfare History Project, Virginia Commonwealth University, https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/religious/the-amana-colonies-a-utopian-community/, Accessed 28 June 2022. ↩︎

“History of the Seven Villages,” Amana Colonies, https://amanacolonies.com/visitors-guide/history-of-the-seven-villages/ Accessed 23 June 2022 ↩︎