Schedule Spotlight: Watervliet Shakers

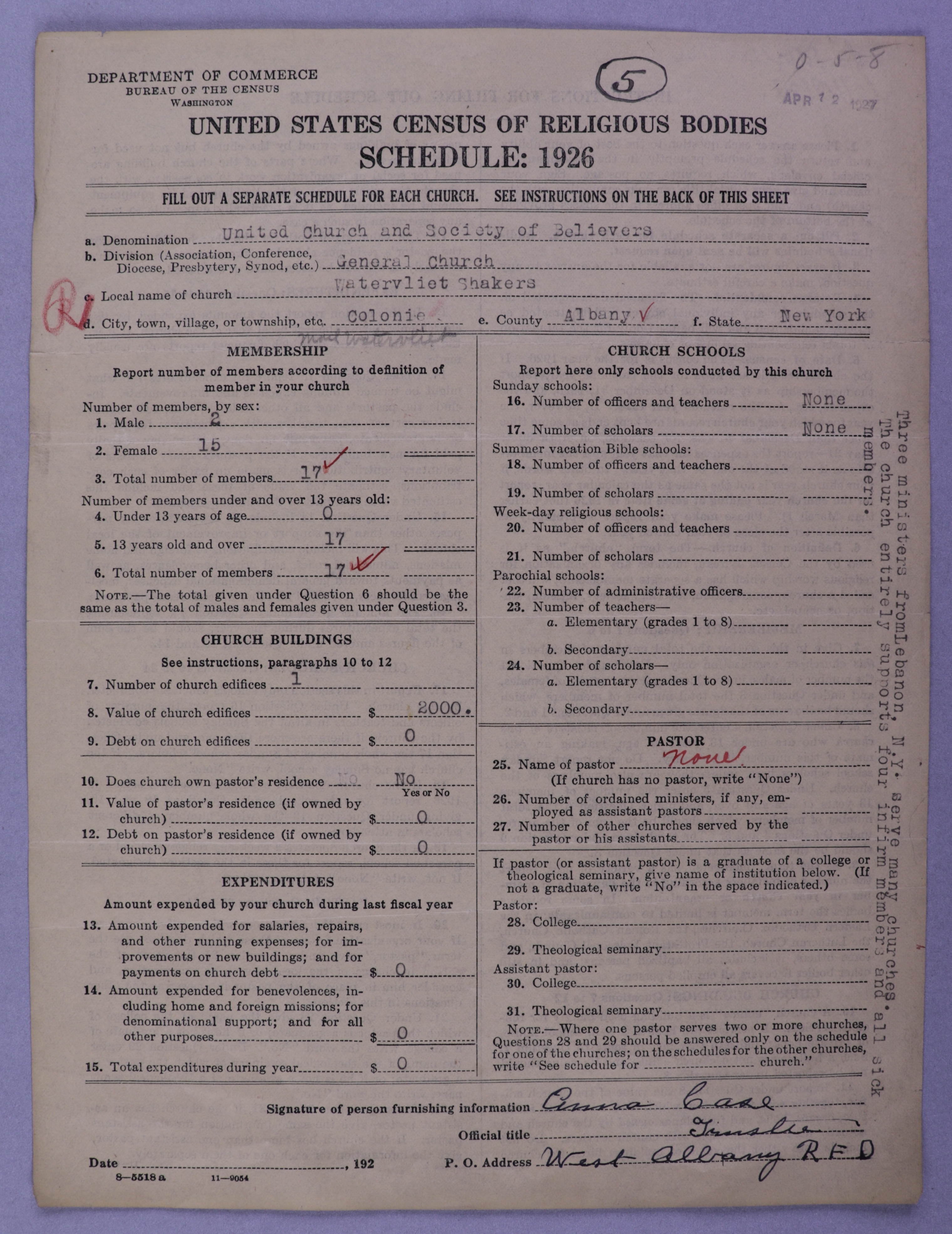

This month we are featuring a schedule from the United Church and Society of Believers (in Christ’s Second Coming), more commonly known as the Shakers. This community, located in Colonie (or West Watervliet), New York, is the site of the first community of Shakers in the United States. This Shaker community had seventeen members, all of whom were over thirteen years old, and fifteen of whom were women. There was no pastor listed on the schedule, but a note on the side stated “Three ministers from Lebanon, N.Y. serve many churches.” This community supported its members in need. The sidenote also stated, “The church entirely supports four infirm members, and all sick members.” Because of the Shaker commitment to communal living, this financial support would have been the norm in all settlements.

Figure 1. The 1926 Census schedule for the Watervliet Shakers in Colonie, New York.

The Shaker religious movement dates to England in the mid-eighteenth century. Two Quakers from Manchester, James and Jane Wardley. One early adherent, Ann Lee, soon became the movement’s leader and became known as “Mother Ann.” One of the most notable attributes of the Shaker movement is their commitment to celibacy; Mother Ann felt called to celibacy after her marriage to Abraham Stanley in 1761 led to all four of her children dying in infancy. She came to believe that sexual intercourse and marriage were sinful. By the 1800s, no married individuals were allowed to live in Shaker communities without both members agreeing to not cohabitate nor have sex.1

Persecution led to the Shakers leaving England and coming to the United States in 1774, and they dispersed across the United States. Lee and seven followers settled in Watervliet in 1776.2 It was only at this point, in Watervliet, that the Shakers embraced communitarianism.3 Beyond celibacy and communalism, another important tenet of Shakerism is that Mother Ann Lee was the second coming of Jesus Christ.4 Shakers often faced persecution for their communal and celibate lifestyle, along with their enthusiastic and bodily method of worship.5 The name Shakers actually came from the term “Shaking Quakers,” commonly used in the early years.

![Figure 2. A group of Shakers posing for a postcard photograph in Troy, New York in the 1870s. Note the clothing and the preponderance of women to men. Photo from the Library of Congress. [Irving, James E., ‘Group of Shakers’, between 1870 and 1880, Photograph, Washington D.C , Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.]](/blog-img/postcard-shakers.png)

Figure 2. A group of Shakers posing for a postcard photograph in Troy, New York in the 1870s. Note the clothing and the preponderance of women to men. Photo from the Library of Congress. [Irving, James E., ‘Group of Shakers’, between 1870 and 1880, Photograph, Washington D.C , Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.]

In the late eighteenth century, Shaker growth led to the establishment of other settlements in New England and beyond. The Mount Lebanon community in Ohio became the center of Shakerism. In the twentieth century, the decline of the overall Shaker population affected Watervliet. In the 1920s, an outside person was hired to manage the farm, and in 1926, part of the property was sold to New York state, including huge barns built only the decade before in the hopes of expansion.6 The community still at Watervliet in 1926, when the census gathered information, would have lived only in the South Family part of the settlement. By 1938, the society no longer owned any of the Watervliet settlement.7 However, Watervliet remained an important Shaker site, with Mother Ann Lee and other leaders buried on the grounds. Today, the settlement is a historic district.

Anna Case, who listed herself as “Trustee” on the Official Title line, filled out the schedule for the Watervliet Shakers. Case was also listed as “head of household” for the 1920 Census, which listed thirty members, including Case, living at the commune, including four children under the age of thirteen.8 Case was the last Eldress of the Watervliet Shakers, heralding the group in their last decades at the settlement. She was around seventy-years old in 1926 and had been a part of the society since she was around eleven years old and ran away from her abusive household.9 She found the community while seeking shelter, then converted and remained as a member. Case became a leader of the community in early adulthood, assisting other eldresses before being promoted as the Trustee in 1915, meaning she was in charge of all business at the settlement.10

![Figure 3. The school house at the Watervliet Shaker community in Colonie, New York. The school closed after 1926. Photo from the Library of Congress. [Historical American Buildings Survey, “Shaker Schoolhouse, Watervliet Shaker Road, Colonie Township, Watervliet, Albany County, NY”, after 1933, Photograph, Washington D.C., Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division].](/blog-img/shakerschoolhouse2.png)

Figure 3. The school house at the Watervliet Shaker community in Colonie, New York. The school closed after 1926. Photo from the Library of Congress. [Historical American Buildings Survey, “Shaker Schoolhouse, Watervliet Shaker Road, Colonie Township, Watervliet, Albany County, NY”, after 1933, Photograph, Washington D.C., Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division].

The decline of the Watervliet Shaker settlement was piecemeal. The western portion of the settlement, called the Watervliet West Family, closed in 1916, and later the northern portion, the North Family, was sold. In 1922, the Church Family property could not be maintained, but there was no consensus about leaving the settlement; the sale of land was put off until 1925. In 1926, the school located at the settlement was closed, and the few children who remained as boarders were sent away; this explains why there were no children listed as part of the community on the schedule.11 In the 1930 Census, there were fewer members than in 1926 - only thirteen.12 Women still outnumbered men, with two men and eleven women, and no one under the age of twenty.

Case would have been no stranger to closing Shaker communities; a Shaker Heritage website reads: “Lucy Bowers’ diary entry for July 3, 1919 notes, “Eldress Anna goes with the [Lebanon] Ministry to the North [Family]. Another tortuous move instituted.” She refers to the process of closing the Watervliet North Family. By the time of this diary entry, Anna Case had been involved in closing three communities.” Case would have dealt with the sale and closing of parts of the settlement through the 1920s and 1930s, until her death in 1938.13 That the year of her death coincided with the final loss of property at Watervliet is notable.

Though the Watervliet Shakers were already facing decline in the 1920s, that the community still provided financially for infirm and sick members meant that they held true to their communal ideals. The case would have worked to maintain that security for those members who could no longer work and still provide for those who could. Also, it was important enough to add a note to the schedule to supplement other information that the Census Bureau did ask for. Interestingly, the community wrote that during the year, the amount of expenditures for the church was $0. Perhaps, since Shaker settlements were mostly self-sufficient and produced their own food and goods, they kept the financial side of the settlement away from the church. Either way, the community prioritized providing for all in their community, a tradition since 1776.

Lionel Laborie, “Shakers,” Oxford Bibliographies, Last Modified 31 July 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199730414-0319 Accessed 11 April 2022. ↩︎

Cornelia E. Brooke, “Watervliet Shaker Historic District,” National Registration of Historic Places Nomination Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973), Section 7. ↩︎

Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, (Yale University, 1972,) 492-3. ↩︎

Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 494. ↩︎

Elizabeth Freeman, “The Rhythm of Shaker Dance Marked the Shakers as “Other,”" JSTOR Daily, 21 August 2019. ↩︎

Brooke, “Watervliet Shaker Historic District,” National Registration of Historic Places Nomination Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973), Section 8. ↩︎

Brooke, “Watervliet Shaker Historic District,” National Registration of Historic Places Nomination Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973), Section 8. ↩︎

Year: 1920; Census Place: Colonie, Albany, New York; Roll: T625_1083; Page: 8A; Enumeration District: 151. Ancestry, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎

Lorraine Weiss, “The Last Eldress of the Watervliet Shakers Eldress Anna Case (1855-1938),” Shaker Heritage Society, 6 November 2020, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎

Weiss, “The Last Eldress of the Watervliet Shakers Eldress Anna Case (1855-1938),” Shaker Heritage Society, 6 November 2020, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎

Weiss, “The Last Eldress of the Watervliet Shakers Eldress Anna Case (1855-1938),” Shaker Heritage Society, 6 November 2020, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎

Year: 1930; Census Place: Colonie, Albany, New York; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 0129; FHL microfilm: 2341140. Ancestry, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎

Year: 1930; Census Place: Colonie, Albany, New York; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 0129; FHL microfilm: 2341140. Ancestry, Accessed 13 April 2022. ↩︎