What can you learn from a census schedule?

The Census Bureau spent a great deal of effort in designing the schedules, or forms, that it sent out to hundreds of thousands of congregations for the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies. Those forms were the primary mechanism by which the Bureau gathered data. They were also the primary expression of what the Bureau thought religion was: what about it was worth counting, and which groups counted as a religion.

Let’s take a close look at the single census schedule reproduced below. Leaving the question of which religious groups the Census Bureau decided to count for a different time, we can ask two questions. What was the Bureau trying to measure about American religious groups? And what can historians, religion scholars, genealogists, and local researchers learn from these schedules?

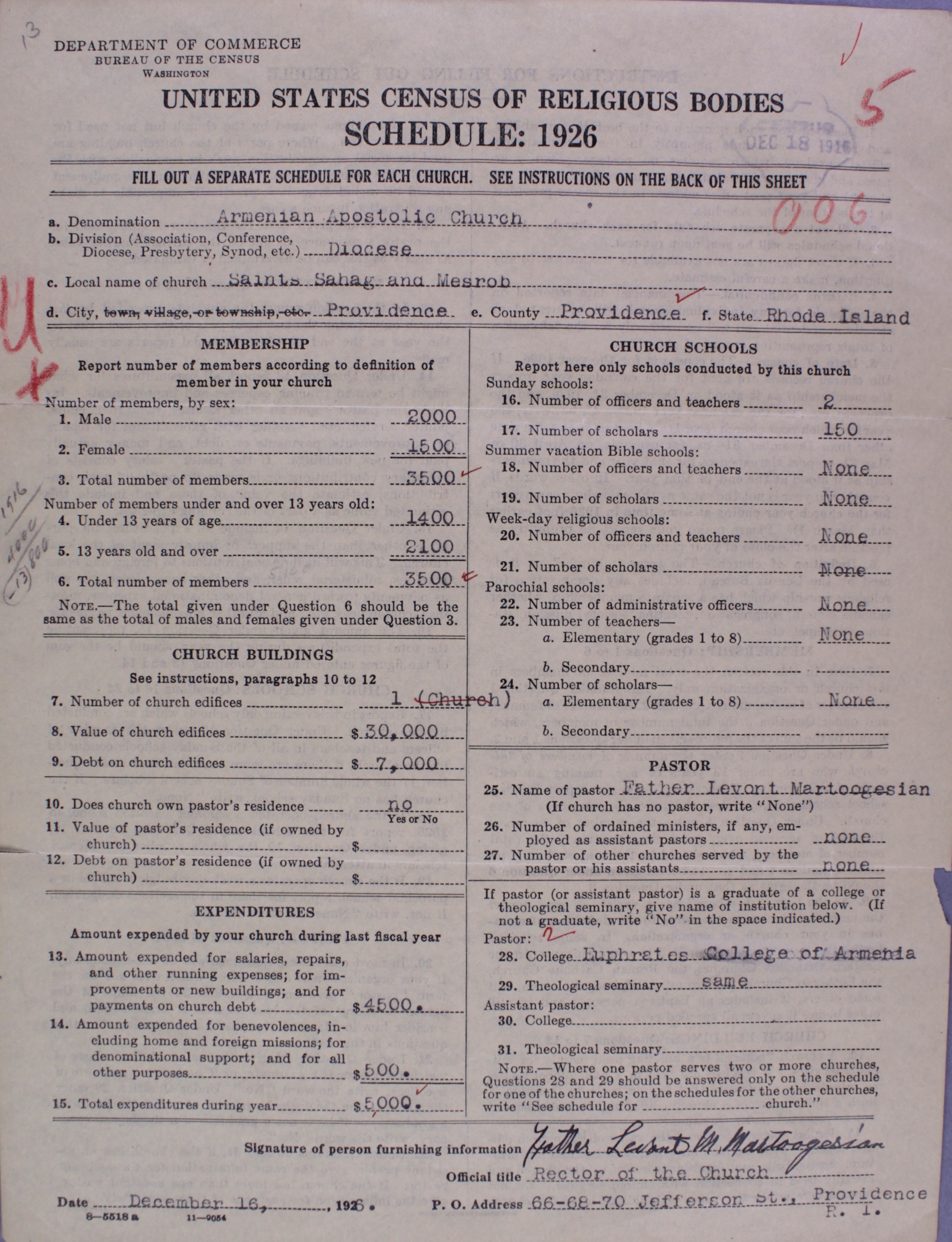

Figure 1. A schedule filled out by an Armenian Apostolic Church in Providence, Rhode Island, for the 1926 Census of Religious Bodies.

Each schedule is a form intended to be filled out by “each church.” The congregation, parish, or church is therefore the basic unit of the Religious Bodies census. The Bureau chose to count churches, rather than individuals or households as they did in the population censuses. This system worked best for Protestant denominations that were organized into congregations. Other groups—Christian and non-Christian—had to fit within that mold in order to be counted. But it is worth noting that the Census Bureau was at least aware of this problem. In the case of American Jews, it was willing to print a different form, using a language other than English and modifying the questions so they did not assume a Christian organization.1

The census form asks a number of questions, some that identify the congregation, others that describe its membership, its buildings and finances, its educational programs, and its leadership. Though this particular schedule was filled out with a typewriter, most schedules were filled out by hand. In addition to the information that the congregations provided to the Census Bureau, there are also markings on the form from the Census Bureau itself, usually written in red pencil or ink or stamped on the form. These markings uniquely identify the schedule. They also provide information about how the Census Bureau processed the schedule, such as the date it was received in the mail and whether an agent had to follow up for further details. Those markings also standardize the answers that were provided on the form so that the data could be accurately transferred to punch cards and tabulated. For instance, on this schedule, the Census Bureau checked that the number of male and female members summed up to the correct total and crossed off some irrelevant clarifications from the person who filled out the form.

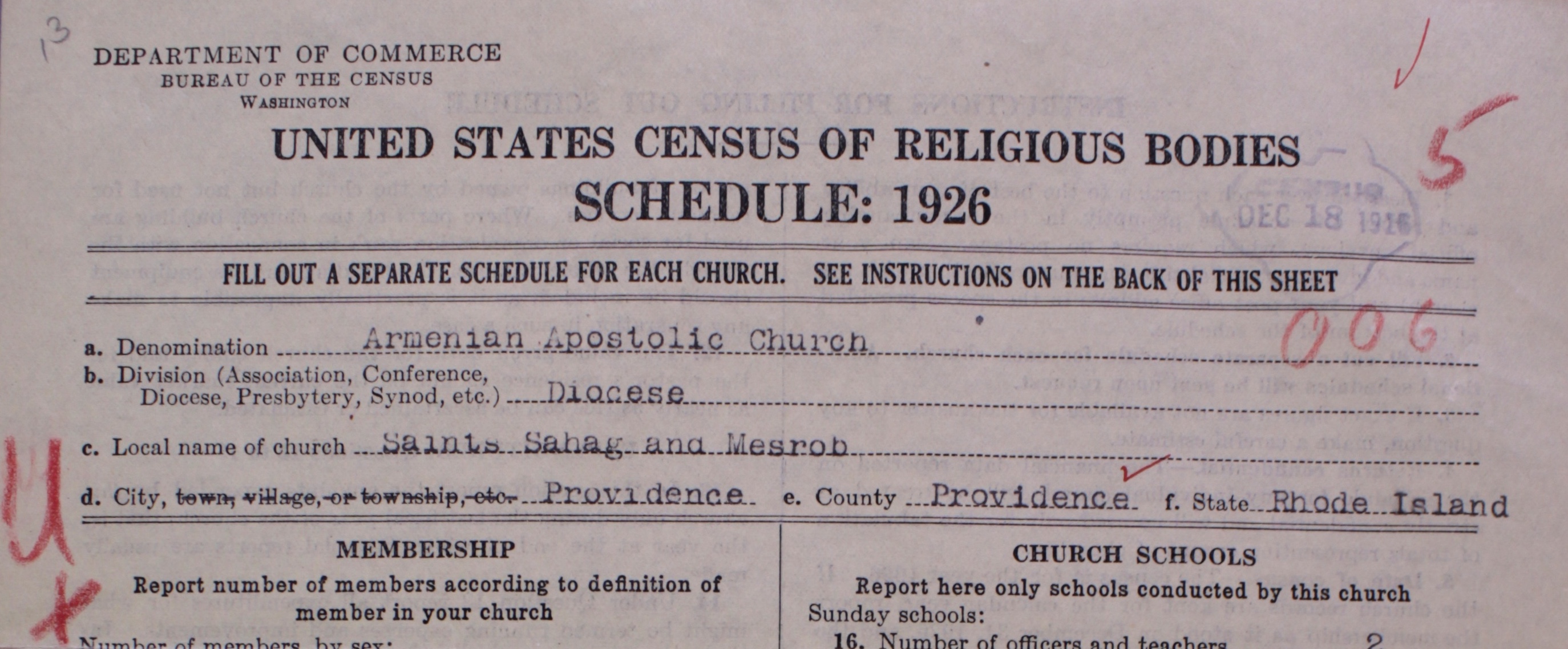

Figure 2. The head of a census form identified the specific congregation, its geographic location, and its place in its denomination’s organizational structure.

The head of the form asks a series of questions that identified the name of the church, placed it within a denomination and possibly within a smaller grouping within that denomination, and identified its geographic location (figure 2). Notice also the stamp with the date that the schedule was received, two days after it was filled out by the congregation.

This schedule identifies the Church of Saints Sahag and Mesrob in Providence, Rhode Island. The congregation described itself as a part of the Armenian Apostolic Church. That church was an ancient church, having achieved something like its current ecclesiastical structure in the fourth century. It was unusual, at least in the United States, for being associated with neither the Protestants, nor the Roman Catholics, nor the Eastern Orthodox churches. Rather, the Armenian church never accepted the description of Christ’s two natures propounded at the Council of Chalcedon, but it also did not accept the theological proposals of the monophysites. It might most properly be described as a holding to miaphysitism, the belief that Christ has one incarnate nature that is a union of both divine and human natures.2 Members of this church came to the United States in significant numbers starting in the 1880s and 1890s, then in rather greater numbers following World War I and the Armenian genocide.

The congregation thus regarded itself as part of an ancient church which looked back to Armenia for ecclesiastical leadership. This schedule thus draws our attention to the presence of a religious tradition in the United States which is—it is safe to say—virtually unmentioned in the historiography of American religion. It identified its American organization as simply a diocese (also called an eparchy) within that global structure.

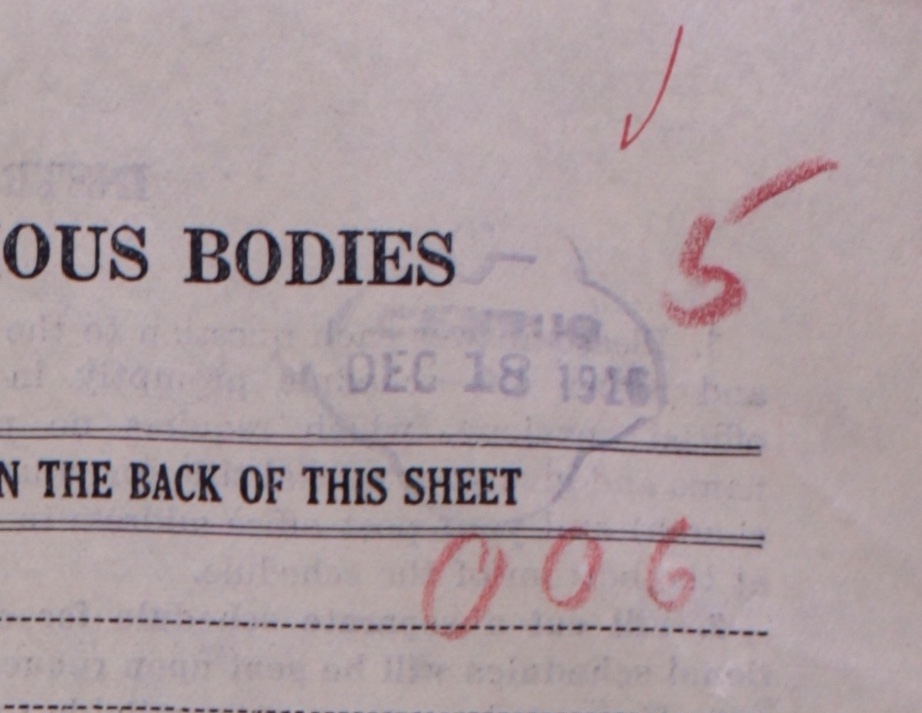

Figure 3. The marking ‘006’ was an identifier for the Armenian Apostolic Church, and the number ‘5’ was an identifier for this schedule within that denomination.

The red pencil and ink markings by the Census Bureau show, however, how that agency had to fit that church into an American context (figure 3). The number “006” (which the Bureau more commonly wrote as “0-0-6”) uniquely identifies the denomination to which this congregation belonged. The Bureau counted some 214 denominations in the 1926 Census. In general this was a technique that the Bureau used to standardize names of denominations. For instance, one congregation might write “Southern Baptist” and another “Southern Baptist Convention,” but both congregations belonged to the same unit. In this case, however, the standard name that “0-0-6” referred to was the Church of Armenia in America. In other words, where the congregation thought itself as part of a global communion, the Census Bureau counted it as part of an American organization.

The Census Bureau gave this congregation the ID number “5,” a number that was unique within that denomination. These IDs are invaluable for keeping track of the hundreds of thousands of schedules. But those ID numbers remind us to think about this congregation in the context of others within its denomination. For instance, the red “U” to the left of the schedule indicates that the Census Bureau identified this congregation as being a part of an urban, as opposed to a rural, congregation (figure 1). Was it typical for the Armenian Apostolic Church to be located in cities? Was this church close to others in New England, or was it geographically isolated? How many Armenian Apostolic churches were there in the United States?

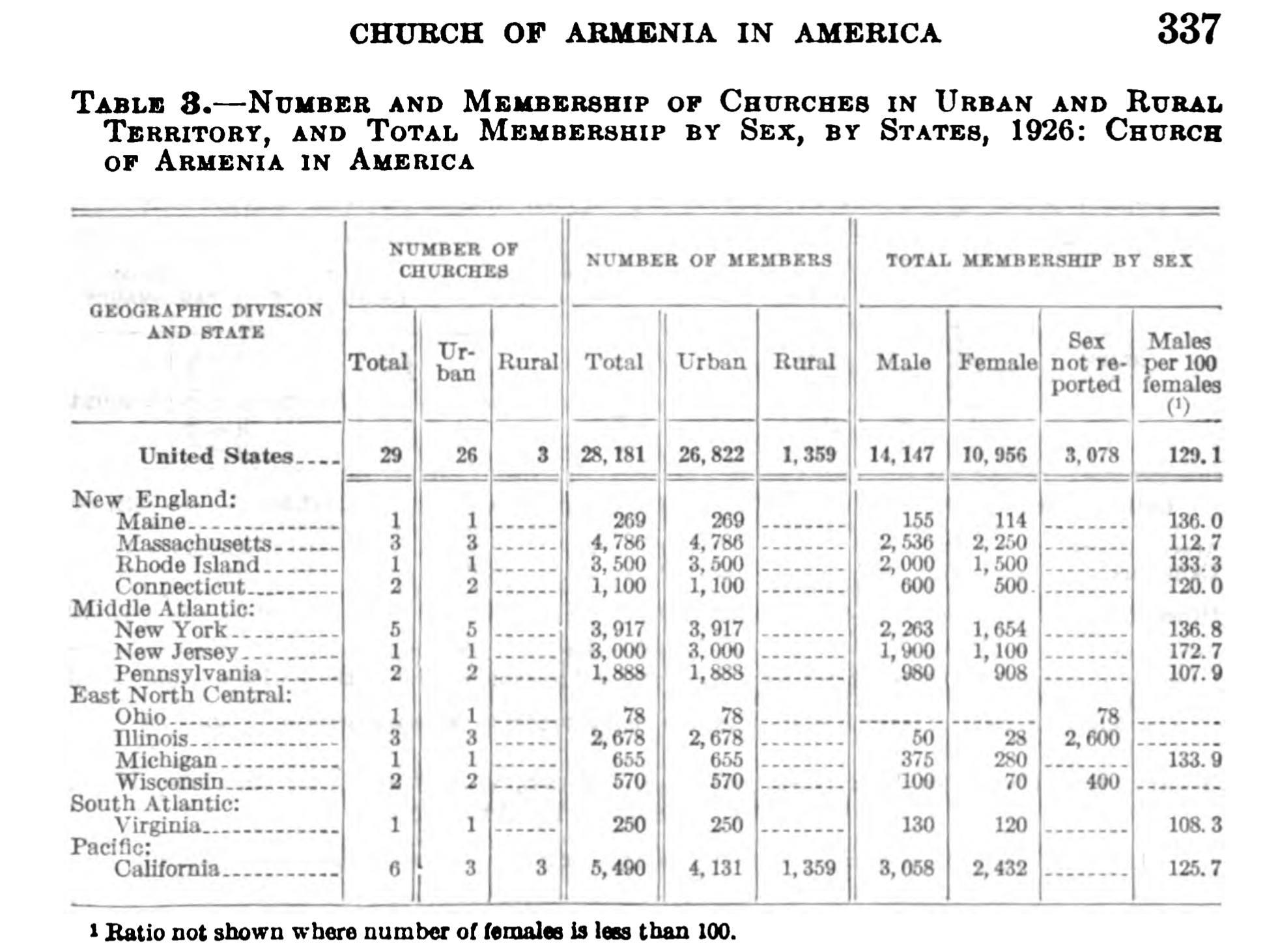

Figure 4. A table from the published census reports, showing the breakdown of congregations in the Church of Armenia in America by region and by whether they were urban or rural. Source: Religious Bodies: 1926, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (Government Printing Office, 1930), 2:337.

We can answer those questions by looking at the aggregated numbers that the Census Bureau calculated (figure 4). We learn that there were 29 Armenian Apostolic Churches in the United States, of which seven were in New England and all except three of which were in cities.3 The overall picture shows a small denomination, scattered around the country but predominantly in urban centers, presumably because its members were mostly immigrants.

That is what we can learn from the aggregated data, but a far more detailed picture is available if we look at the schedules individually. Rather than simply knowing that this church was in an urban area, we know that it is in the city of Providence. The Census Bureau published detailed tables with the number of churches by denomination in major cities, which included Providence. But these schedules contain information about the specific city, town or village in which a church was located, even for the most rural and remote of churches. We can thus have vastly more specific information about the geographic location of each congregation. In time, for instance, we could also learn about the three rural congregations in California, since members of those churches must have comprised a large portion of the neighboring population.

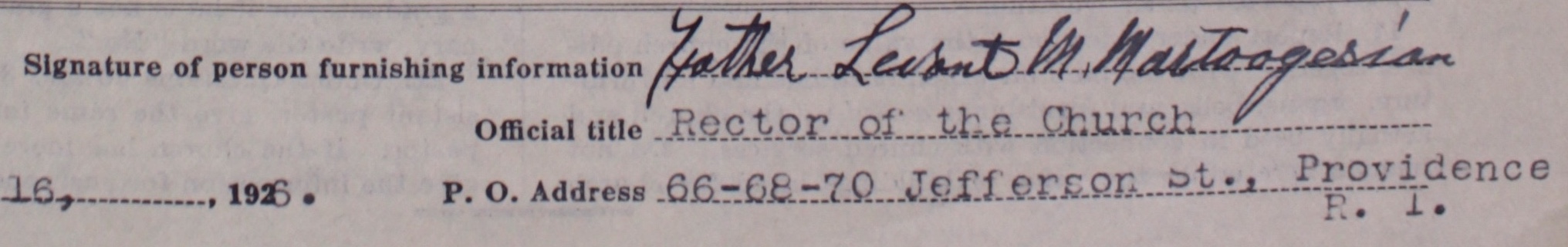

Figure 5. Sometimes the census schedules contain the specific address of a congregation, in addition to the city-level data at the top of the schedule. This schedule shows the street address of the church in Providence.

In this particular case, we are fortunate to know not only the church’s city, but also its address. The form contains a place for recording the address of the person who filled out the form. These elements were not originally considered data by the Census Bureau. They do not always contain addresses, since the name of the church and the town might have been sufficient for correspondence. And sometimes the forms were filled out by central denominational authorities, as was the case for the Latter-day Saints. However, in this case the specific address of the church on Jefferson Street is available, placing it at a specific location within the city. Indeed, that church still stands on that same location in Providence.

With further research, it would be possible to investigate that congregation’s position within the religious ecology of the city. For instance, the parish’s history records that it purchased its building in 1913 from the former Jefferson Street Baptist Church. This congregation was fortunate to have its own building. The official description of the denomination, approved by the primate of the Church of Armenia in America and published by the Census Bureau in its official records, noted that “pending the building of churches, arrangements have frequently been made with the rectors of Episcopal churches for weekly services, to be conducted by Armenian pastors for their congregations.” Other congregations made more temporary arrangements: “halls have been rented and fitted up as churches, and regular weekly services have been conducted in them.”4 The sharing of church buildings by different religious groups, as well as the exchange of property when one group moved elsewhere or met its demise, were common practices. Identifying them reveals the ways that religious groups occupied different niches within the ecologies of the city.

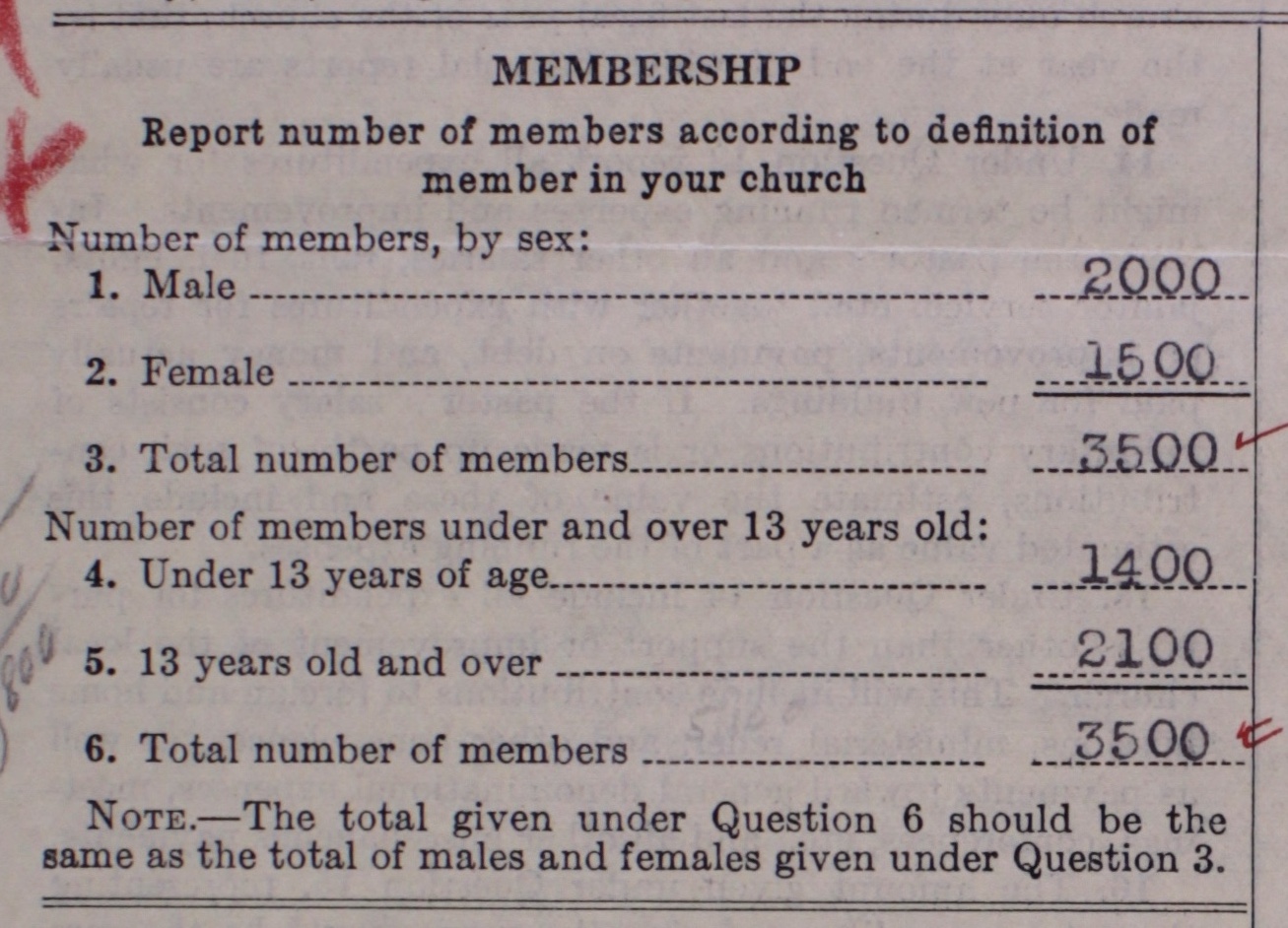

Figure 6. The membership figures were reported for the total membership, as well as broken down by sex and age. This congregation was rather unusual in the American context for having more male than female members.

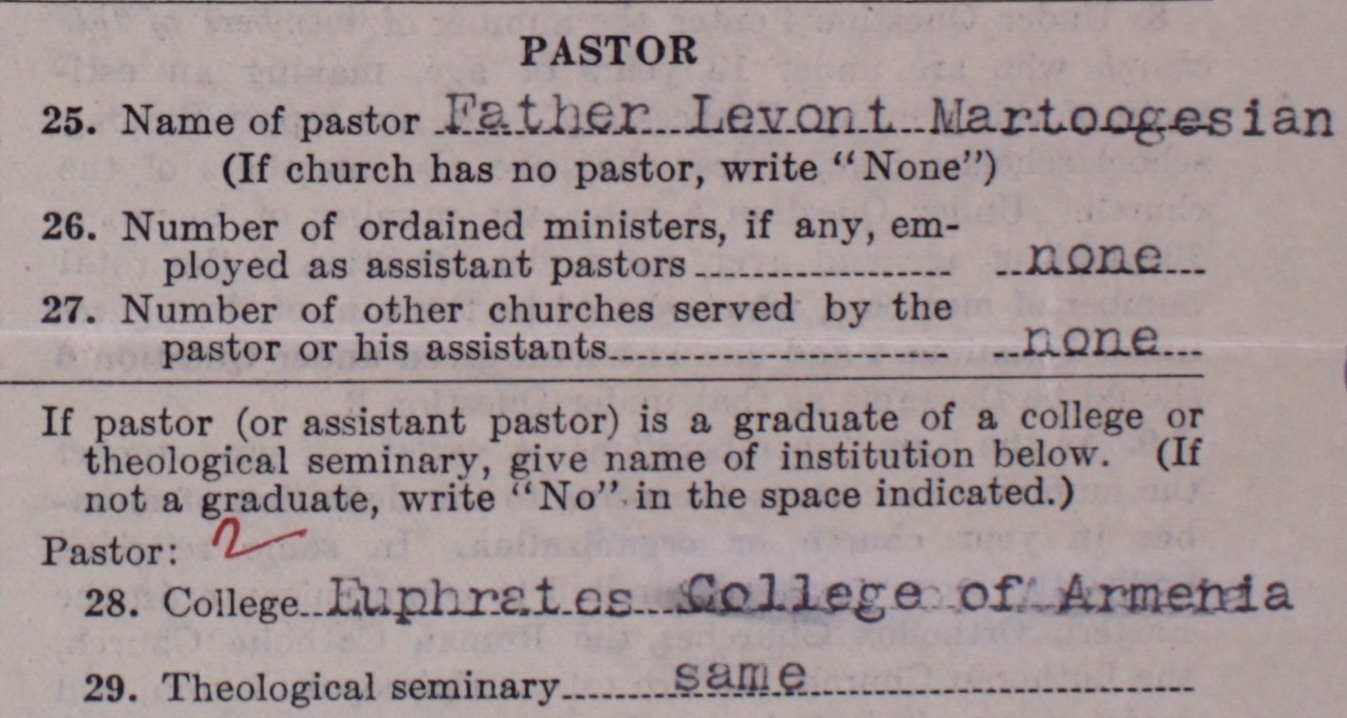

Finally, we can look at quantitative information present on the form (figure 6). For the most part, this information is fairly straightforward: the number of members, the financial information about the church, the number of church schools, and information about the pastor and his education. To be sure, these are not the questions that a religion scholar would ask if they hypothetically had the full force of the federal government behind their attempt to gather data about American religion. But with some historical imagination, we can use the questions that the Census Bureau did ask as a proxy for questions that we do care about. The number of members could be used to understand the extent to which people in a given location were members of a formal religious institution, especially if combined with local population data. That membership is further broken down by sex, allowing us to ask some questions about the varying degrees of participation by men and women across denominations and places. For instance, this church was unusual for having more male than female members, given that most American congregations were predominantly female. The questions about church buildings and finances seem to have been chosen by analogy to other census questions about manufactures and agriculture. But we can use them as a rough proxy for the wealth and class status of congregations. It will also be possible to estimate the proportion of churches that had ministers, how well educated those ministers were, and whether they pastored multiple churches.

Figure 7. Census schedules usually identified the pastor of a congregation. The pastor of this church seems later to have had a checkered career, having been defrocked, imprisoned for extortion and threats of assassination, and shot by an assailant.

Conspicuously absent from the form itself are any questions about race. That omission is all the more stark given that the population census had as its very rationale the counting of free and enslaved people because of the three-fifths clause for Congressional apportionment. The Bureau did classify specific congregations by race, and it was also aware that some denominations were predominantly black or predominantly white. Since that process was not present on the schedules themselves, we will take it up in a subsequent blog post.

The final thing to note about this quantitative information is that knowing the congregation-level data allows scholars to learn things about religious groups that the published aggregates cannot tell us. The Census Bureau aggregated the data for the purposes that they cared about, and it is obviously impossible to work backward from those published aggregates to the lower-level data. But with the lower-level data in hand, it is possible to ask questions of it that the Census Bureau never did. For instance, the Census Bureau published summary statistics of membership, such as the total or average number of members by denomination. With the schedule-level data, however, we could ask questions about the statistical distributions of data such as membership. In other words, we could know not just what the average was, but the entire range of variation in membership for a congregation. For instance, the Chuch of Saints Sahag and Mesrob reported 3,500 members. Was that at the upper end or the lower end of the distribution for that denomination? (Presumably the upper end, but by how much?) With schedule-level data we would also be able to break up the data into different subsets. Was 3,500 members high for Providence? For all cities? Was it high for comparable denominations?

These schedules are thus a rich source for understanding American religion. Understanding what we want to learn from them rather than taking them at face value is necessarily complicated by the questions that the Census Bureau asked and the way that they as a state agency conceived of religion. But these schedules represent the most comprehensive and detailed set of information historians are likely to have available, covering a wide range of denominations from nearly every place in the United States.

See our earlier post about American Jews and the Religious Bodies census. ↩︎

Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (Penquin, 2008), 239. ↩︎

The Census Bureau defined “urban” as a place having more than 2,500 inhabitants. ↩︎

Religious Bodies: 1926, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (Government Printing Office, 1930), 2:340. ↩︎